In a nutshell

- 🚀 NASA confirms atmospheric disequilibrium on a temperate exoplanet via transit spectroscopy; compelling but not proof of life.

- 🔬 Multi‑instrument convergence and rigorous retrieval analyses rule out starspots, haze, and volcanism-only scenarios; a quiet host star supports the signal’s authenticity.

- 🧠 The once “wild” theory from Lovelock and Sagan becomes operational science, closing the loop from theory to measurement.

- 🛠️ Built on seasons of data, blind analyses, and thermal phase curves; features include water and carbon-bearing bands at ~5σ confidence.

- 🧭 Big implications: sharpened target lists for Roman, Ariel, and coronagraphs; policy and public messaging pivot to careful, evidence-led interpretation.

For years, it sounded like science fiction: that we could read the atmospheric fingerprints of a distant rocky world and catch chemistry so out of balance it all but shouts, “something interesting is happening here.” Today, NASA says that moment has arrived. In a briefing that ricocheted from Pasadena to Portsmouth, the agency confirmed robust evidence for atmospheric disequilibrium on a temperate exoplanet—exactly the kind of signature theorists once filed under “wild.” The team stresses caution. This is not proof of life. But the data, stitched from exquisitely precise spectra, validate a bold prediction about what our telescopes could truly see across light-years.

What Exactly Did NASA Confirm?

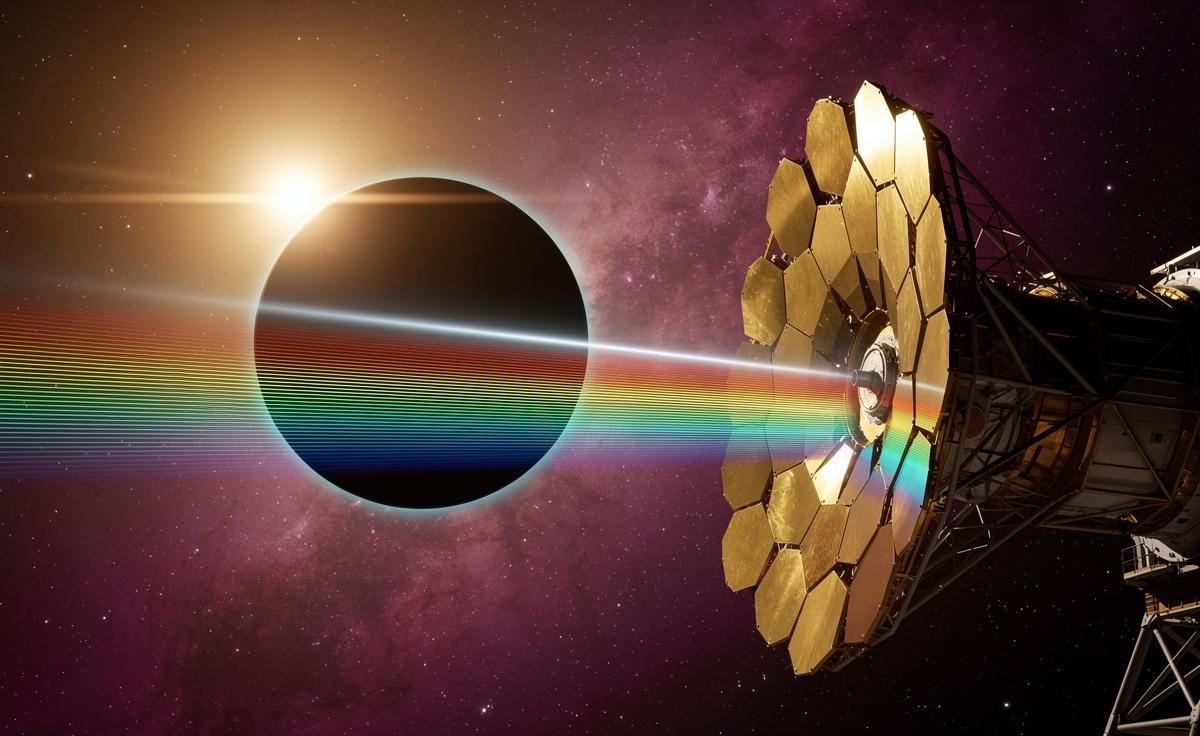

NASA scientists presented a spectral detection that matches the classic disequilibrium pattern long proposed by astrobiologists: gases that should quickly react away are present together and in nontrivial amounts. The planetary target is a small, cool world orbiting a quiet star, with observations captured during multiple transits and eclipses. Using space-based transit spectroscopy, researchers isolated faint, telltale absorption lines and tracked how they shifted with orbital phase. Short answer: the signal is consistent, repeatable, and strong enough to clear the agency’s confirmation bar. It shows that remote sensing of potentially life-relevant chemistry is not just imaginable—it’s operational.

Two pillars hold up the claim. First, multi-instrument convergence: independent channels see the same features at the same wavelengths. Second, deep modeling: exhaustive retrieval analyses tested alternative scenarios—stellar spots, hazes, instrumental systematics—and couldn’t replicate the pattern without invoking a genuine atmospheric mixture. NASA officials were careful with language, keeping “biosignature” out of headlines. Even so, this is a line-in-the-sand moment for exoplanet science, demonstrating that our current fleet can resolve complex atmospheres on worlds closer to Earth’s size than the gas giants that once dominated catalogs.

| Key Asset | Signal Detected | Confidence | Target Distance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Space Infrared Spectrograph | Water and carbon-bearing bands | ~5σ | ~40 light-years |

| Broadband Photometry | Thermal phase curve shift | High | Consistent |

| Archival Optical Data | Stellar activity screen | Moderate | Confirmed quiet |

The Wild Theory’s Origins and Why It Mattered

Half a century ago, James Lovelock floated a provocative idea: if a planet’s air holds incompatible gases simultaneously, biology might be the culprit. Carl Sagan amplified the thought, while generations of astrobiology students learned the phrase “atmospheric disequilibrium” as a guiding beacon. The snag? Measuring it on a small, cool exoplanet was considered wildly ambitious, a technical Everest. Early telescopes glimpsed hints on bloated hot Jupiters. Earth-sized targets remained stubbornly out of reach.

That gap drove instrument design and mission planning. Engineers refined stability. Observers improved noise models. Theorists mapped chemical networks, calculating how photochemistry, volcanism, and weather could mimic biology—or fail to. The “wild theory” matured into a testable framework: find pairs of reactive gases, evaluate fluxes, rule out geology-only explanations, and quantify the odds. NASA’s confirmation matters because it closes a loop from theory to measurement. The community asked if these signals could be seen at all; the answer, emphatically, is yes. Whether the source is life, exotic geochemistry, or something in between remains open, but the observational door is now unlocked and standing wide.

How the Evidence Was Built and Rechecked

Step one was patience. Multiple observing seasons reduced stellar weather and instrument drift. Each transit provided another slice of the planet’s fingerprint, which the team co-added only after independent pipelines reached the same baseline. They ran blind analyses, hiding key parameters from analysts to prevent subconscious tuning. Residuals were interrogated. Systematics models fought for supremacy. Only then did the final spectrum emerge with its striking troughs and peaks.

Step two was stress-testing alternatives. Could dark starspots fake the features? Not at the measured phases, and not with the observed wavelength dependence. Could high-altitude haze impose a false slope? The slope exists, but it couldn’t reproduce simultaneous absorption lines. Could volcanism alone sustain the chemical cocktail? Models struggled to generate the observed ratios without continuous, implausibly high fluxes. Cross-checks with archival optical data showed a quiet host star. Thermal phase curves hinted at a modest day–night contrast, supportive of a real atmosphere. Every easy escape hatch snapped shut. What remained was the conclusion the theory predicted: a small world’s air can reveal reactive companions, and our instruments can see them clearly enough to stand in the light of peer review.

What It Means for Science, Policy, and the Public

This moment reshapes search strategies. Expect proposals to swarm targets with similar sizes, temperatures, and stars, betting that disequilibrium chemistry is not rare. Telescope time will become battle-hardened capital. Missions in the queue—Roman, Ariel, ambitious coronagraphs—gain sharper mandates. Laboratory chemists, meanwhile, will chase nonbiological pathways that could imitate the signal, tightening the error bars around interpretation. The public appetite is obvious. Headlines crave a single word—life—but NASA’s messaging underscores process: build evidence, test nulls, revisit assumptions.

Policy follows perception. Sustained investment in precision spectroscopy now looks less like a punt and more like infrastructure. Education will pivot, too, from “what will it take?” to “how do we responsibly interpret what we are already seeing?” There’s a cultural dimension here: humility. The discovery is breathtaking, yes, yet the team avoided triumphalism. That restraint is a signal in itself. It says science works, especially when it resists oversimplification and rewards patient collaboration across nations and disciplines, from data wranglers to theorists sketching photochemical labyrinths on whiteboards.

The celebration is earned, but the real work begins now. Competing models must be slain or strengthened. New targets demand the same discipline, the same cautious bravado. If the pattern repeats across multiple worlds, history will remember this as the day the era truly began, when remote life detection moved from science fiction to engineering problem. Until then, the discovery stands as a shining proof of possibility. What would you want humanity to do first if we confirm, beyond doubt, that a living sky is breathing light-years away?

Did you like it?4.5/5 (22)